The Historical-Grammatical Method: How to Read Prophecy Correctly

1. Introduction

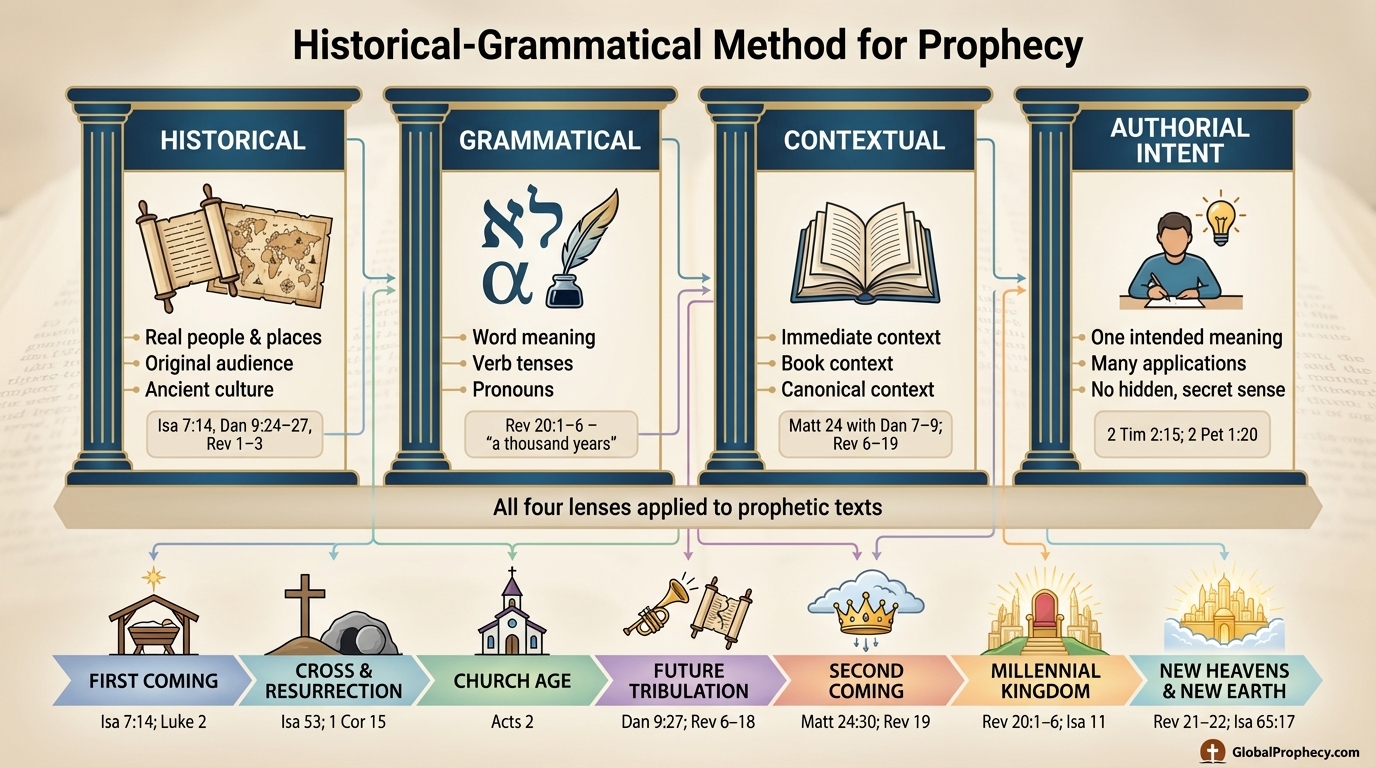

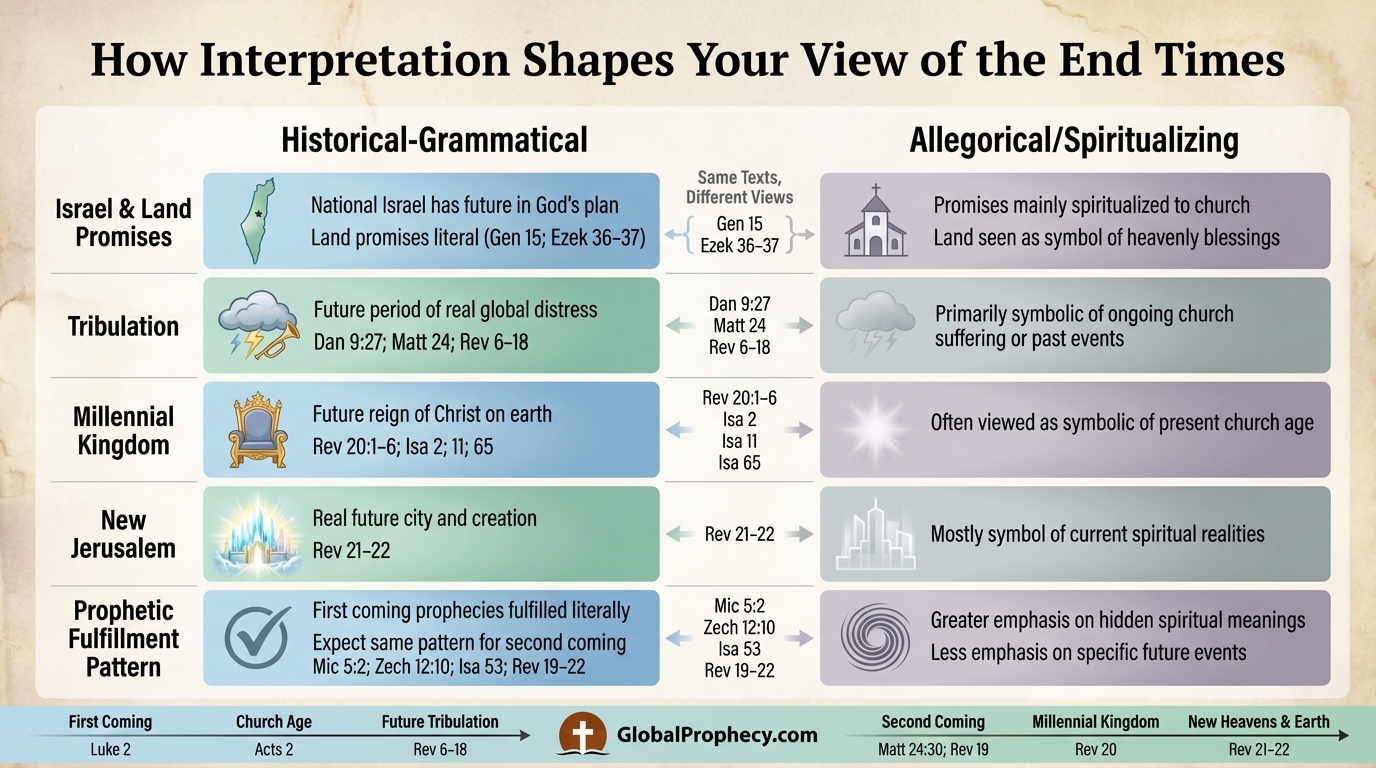

The way we interpret Scripture determines how we understand biblical prophecy. Nowhere is this more obvious than in debates over the millennium, Israel’s future, and the chronology of end-time events. At the center of these debates stands one key question: How should we read prophetic texts?

The historical-grammatical method—sometimes called the literal or normal method—seeks to discover what the biblical author intended to communicate, in his own historical setting, using the normal rules of language. This article explains that method and shows how to apply it carefully and consistently to Bible prophecy.

2. What Is the Historical-Grammatical Method?

The historical-grammatical method is a disciplined way of reading Scripture that aims to uncover the original meaning of the text. It focuses on what the inspired human author actually said, in his time, in his language, in context.

At its core, it asks:

What did this text mean to its author and first readers, according to the normal rules of language and the historical situation in which it was written?

Key features include:

- Historical: Meaning is rooted in real history and real culture.

- Grammatical: Meaning flows from the words, syntax, and literary structure.

- Contextual: Meaning is discovered within immediate and larger biblical contexts.

- Authorial: Meaning is what the author intended, not what later readers wish to find.

- Objective: There is one meaning (though many applications), not endless subjective meanings.

This approach takes seriously Paul’s command:

“Do your best to present yourself to God as one approved, a worker who has no need to be ashamed, rightly handling the word of truth.”

— 2 Timothy 2:15

3. Core Components of the Historical-Grammatical Method

3.1 Historical: Interpreting in Real Space and Time

“Historical” means every prophetic statement was given in a specific setting:

- Who is speaking? (Isaiah, Daniel, John…)

- To whom? (Judah, exiles, churches in Asia Minor…)

- When and where? (Eighth-century Judah, Babylonian exile, first-century Roman Empire, etc.)

- What was happening? (impending invasion, persecution, political upheaval…)

For example, Isaiah 7:14 addresses King Ahaz in a real political crisis. Daniel 9:24–27 is spoken to an exiled people in Babylon. Revelation speaks to seven historical churches in Asia Minor facing persecution and false teaching.

Historical awareness guards us from importing modern ideas (e.g., contemporary politics, technology) directly into the text without warrant.

3.2 Grammatical: Taking Words and Syntax Seriously

“Grammatical” means paying attention to:

- Word meanings in their normal usage

- Verb tenses and moods

- Pronouns (Who is “you”? Who is “they”?)

- Sentence structure and argument flow

Because Scripture is verbally inspired (2 Tim 3:16), the very words matter. For instance, in Revelation 20:1–6, the repeated phrase “a thousand years” must be given its normal numerical sense unless the context clearly demands otherwise.

3.3 Literary and Genre Awareness

The Bible contains various genres—narrative, law, poetry, wisdom, parable, epistle, apocalyptic. Each has its own conventions:

- Apocalyptic (Daniel, Revelation) uses dense symbolism.

- Poetry (Isaiah, Psalms) uses imagery and parallelism.

- Narrative (Genesis, Acts) tells historical events.

Genre awareness does not cancel literal meaning; it clarifies how literal meaning is conveyed. A prophecy in poetic form is still about real events and persons, but expressed with heightened imagery.

3.4 Context: Text in Its Surroundings

Context operates on several levels:

- Immediate context – verses and paragraphs directly around the passage.

- Book context – themes and structure of the entire book.

- Canonical context – the rest of Scripture.

As Peter reminds us:

“No prophecy of Scripture comes from someone’s own interpretation.”

— 2 Peter 1:20

No prophecy is to be isolated from the rest of God’s revelation. Matthew 24, for example, must be read alongside Daniel 7–9 and Revelation 6–19.

3.5 Authorial Intent and Single Meaning

The historical-grammatical method insists each text has one intended meaning (sensus unum), shared by the divine and human authors. That meaning may have:

- Many applications (to different people and circumstances)

- Many implications (truths logically contained in the text)

…but not multiple, contradictory meanings. This rejects the idea that behind the plain sense lies a separate, secret “fuller sense” (sensus plenior) unrelated to what the prophet consciously meant.

4. How the Historical-Grammatical Method Applies to Prophecy

Applying this method to prophecy means taking prophetic texts as seriously as we take historical narrative or epistles.

4.1 Literal, Not Allegorical—But Not Wooden

“Literal” here means normal or plain interpretation—not “flat” or “wooden.” The historical-grammatical method:

- Recognizes figures of speech, metaphors, and symbols.

- Insists those figures point to real, literal referents.

- Refuses to bypass the plain sense in favor of hidden, esoteric meanings.

Examples:

- When Jesus says, “I am the door” (John 10:9), no one imagines a literal piece of wood. We naturally understand this metaphor to express a literal truth about Christ as the exclusive entry to salvation.

- When Isaiah 11:1 speaks of a “shoot from the stump of Jesse,” we rightly see a figure for a real person—the Messiah in David’s line.

In prophecy, the same rule holds: imagery serves literal truth; it does not cancel it.

4.2 Symbols and Images: Discovering Their Literal Referents

Prophetic literature is rich with symbols—beasts, horns, stars, lampstands, bowls, trumpets. The historical-grammatical method asks:

-

Does the text interpret its own symbol?

- The seven stars are “the angels of the seven churches” (Rev 1:20).

- The many waters are “peoples and multitudes and nations and languages” (Rev 17:15).

-

Is the symbol explained elsewhere in Scripture?

- Eagle’s wings in Revelation 12:14 echo Exodus 19:4 and Isaiah 40:31, pointing to God’s powerful care and deliverance, not to a modern air force.

-

Does historical-cultural background clarify it?

- Horns symbolizing kings and power (Dan 7–8) draw on ancient Near Eastern imagery, where horns represented strength and dominion.

In every case, symbols point to concrete entities, events, or qualities. They are not a license to let imagination roam.

4.3 Prophetic “Mountain Peaks” and Time Gaps

Old Testament prophets often saw future events like distant mountain peaks—distinct summits appearing close together, with the valleys (time gaps) between them hidden.

Examples:

-

Isaiah 61:1–2: Jesus reads the first part in Nazareth (Luke 4:18–21) and declares, “Today this Scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing,” but stops before “the day of vengeance of our God.”

- The first clause: fulfilled at Christ’s first coming.

- The following clause: awaits His second coming.

-

Zechariah 9:9–10: Verse 9 describes the humble King on a donkey (fulfilled at the triumphal entry), while verse 10 leaps to His worldwide reign—separated by the entire church age.

The historical-grammatical method acknowledges these intervals by comparing passages across the canon, not by collapsing everything into a single “spiritual” fulfillment.

4.4 Comparing Prophecy with Prophecy

Because all Scripture shares one divine Author, prophecy must be read with prophecy:

- The “abomination of desolation” in Daniel 9; 11; 12 is explained and applied by Jesus in Matthew 24:15.

- The “thousand years” of Revelation 20 must be studied alongside numerous Old Testament kingdom promises (e.g., Isaiah 2; 11; 65; Jeremiah 31; Ezekiel 36–37).

This comparison:

- Guards against building a theology on a single verse.

- Ensures one prophecy is not interpreted in a way that contradicts another.

- Allows later revelation (e.g., the New Testament) to clarify earlier prophecy without overturning its plain sense.

4.5 Fulfilled Prophecy as a Guide to Unfulfilled Prophecy

Historically, fulfilled messianic prophecies were fulfilled literally:

- Virgin birth (Isaiah 7:14 → Matthew 1:22–23)

- Birth in Bethlehem (Micah 5:2 → Matthew 2:5–6)

- Piercing (Zechariah 12:10 → John 19:37)

- Suffering servant (Isaiah 53 → 1 Peter 2:22–25)

- Timing of His death (Daniel 9:24–26)

This consistent literal fulfillment sets a hermeneutical precedent: prophecies of Christ’s second coming and the end times should likewise be expected to be fulfilled literally, unless the text itself clearly indicates otherwise.

5. Practical Steps for Reading Prophecy with the Historical-Grammatical Method

When you open a prophetic passage, you can apply the method in a simple, structured way:

-

Identify the genre and setting.

Is this apocalyptic (Revelation), poetic (Isaiah), or narrative (Matthew 24)? Who is addressed? When? -

Read the passage repeatedly in context.

Trace the flow of thought. What problem or promise is being addressed? -

Observe the grammar carefully.

Note key terms, repeated phrases (e.g., “day of the LORD”), time indicators, pronouns, and logical connectors. -

Distinguish literal from figurative language.

- Ask: Does the literal sense make good sense here?

- If not, is this obviously symbolic (e.g., a seven-headed beast)?

- Does Scripture elsewhere interpret this symbol?

-

Compare related prophecies.

Use cross-references: Daniel with Matthew 24; Isaiah with Revelation; Old Testament promises with New Testament allusions. -

Ask what the original audience would have understood.

What would ancient Israel have heard in Isaiah 2 or Ezekiel 37? What would first-century churches have heard in Revelation 2–3? -

Draw theological and practical applications.

After grasping the original meaning, ask: How does this shape my hope, holiness, worship, and mission today?

6. Common Errors the Historical-Grammatical Method Avoids

Using this method helps avoid serious interpretive mistakes:

- Allegorizing away plain promises (e.g., turning concrete land and kingdom promises to Israel into mere symbols for the church).

- Subjectivism—making prophecy say whatever “feels right” or fits a system.

- Over-literalism—refusing to recognize legitimate figures of speech (e.g., taking every poetic image as a physical description).

- Proof-texting—lifting verses out of context to support preconceived views.

- Ignoring time gaps—collapsing first and second advent texts into a single event.

By contrast, a disciplined historical-grammatical approach keeps us anchored to what God actually said, in the way He chose to say it.

7. Conclusion

The historical-grammatical method is not a clever modern invention; it is simply reading Scripture as meaningful communication from God in real history, through real human authors, using real language. Applied to prophecy, it calls us to:

- Take prophetic words seriously and normally.

- Respect context, genre, and authorial intent.

- Recognize symbolic language without denying its literal referents.

- Let fulfilled prophecy shape our expectations for unfulfilled prophecy.

When we interpret Bible prophecy this way, we honor both the clarity and the authority of God’s Word. We gain a coherent, hope-filled picture of God’s future plans, and we are better equipped to “pay attention” to the prophetic word, “as to a lamp shining in a dark place” (2 Peter 1:19).

FAQ

Q: What is the historical-grammatical method of interpreting Bible prophecy?

The historical-grammatical method seeks to understand prophetic passages in their original historical setting, according to the normal rules of language and grammar. It focuses on what the inspired author intended to communicate to the original audience, allowing for symbols and figures of speech but insisting they point to real, literal referents.

Q: Does the historical-grammatical method deny that prophecy uses symbols?

No. It fully recognizes that prophecy—especially apocalyptic texts like Daniel and Revelation—uses rich symbolism. However, it insists that those symbols are not free-floating; they refer to literal people, events, or realities, often interpreted within the text itself or elsewhere in Scripture.

Q: How does this method differ from allegorical interpretation?

Allegorical interpretation treats the literal sense as secondary and looks for deeper, hidden spiritual meanings beneath the text, often without objective controls. The historical-grammatical method treats the plain sense as primary and only moves to figurative meaning when the text or context clearly demands it, keeping interpretation anchored to authorial intent.

Q: How do I know when a prophetic passage should be taken figuratively?

Ask whether the literal sense makes coherent sense within Scripture and reality. If not, check whether the passage itself labels something as a symbol, whether Scripture elsewhere interprets it, or whether genre (e.g., poetry, apocalyptic) strongly suggests vivid imagery. Even then, the figure of speech points to a literal truth.

Q: Why is the historical-grammatical method important for end-times study?

Because end-times doctrine rests heavily on prophetic texts, our method of interpretation will shape our entire eschatological framework. The historical-grammatical method provides an objective, text-driven way to handle prophecy, guarding against speculation and ensuring our hope is grounded in what God has actually promised in His Word.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the historical-grammatical method of interpreting Bible prophecy?

Does the historical-grammatical method deny that prophecy uses symbols?

How does this method differ from allegorical interpretation?

How do I know when a prophetic passage should be taken figuratively?

Why is the historical-grammatical method important for end-times study?

L. A. C.

Theologian specializing in eschatology, committed to helping believers understand God's prophetic Word.

Related Articles

How to Interpret Bible Prophecies

How to interpret Bible prophecies with sound hermeneutics. Learn practical principles, context rules, and safeguards for reading prophetic Scripture well.

Literal vs Allegorical: The Right Way to Interpret Bible Prophecy

Literal vs allegorical prophecy: learn how the literal-grammatical-historical method guides when to read Bible prophecy plainly and when symbolically.

The 70 Weeks of Daniel: Understanding Bible's Prophetic Timeline

The 70 weeks of Daniel explain God's prophetic timeline for Israel, Christ's first coming, and a future 70th week leading to the end-time climax.

Babylon the Great

Babylon the Great in Revelation 17–18 reveals end-time religious and commercial rebellion against God and its sudden, final destruction in judgment.