Postmillennialism Examined: Will the Church Christianize the World?

1. Introduction

Postmillennialism claims that the church, empowered by the Holy Spirit and the preaching of the gospel, will progressively Christianize the world before Christ returns. From a premillennial, grammatical–historical reading of Scripture, this vision is attractive but ultimately unsustainable biblically.

This article will (1) define postmillennialism, (2) summarize its main biblical arguments, and (3) offer a concise, Scripture-based critique—focusing on whether the church will in fact usher in a golden age before the second coming of Christ.

2. What Is Postmillennialism?

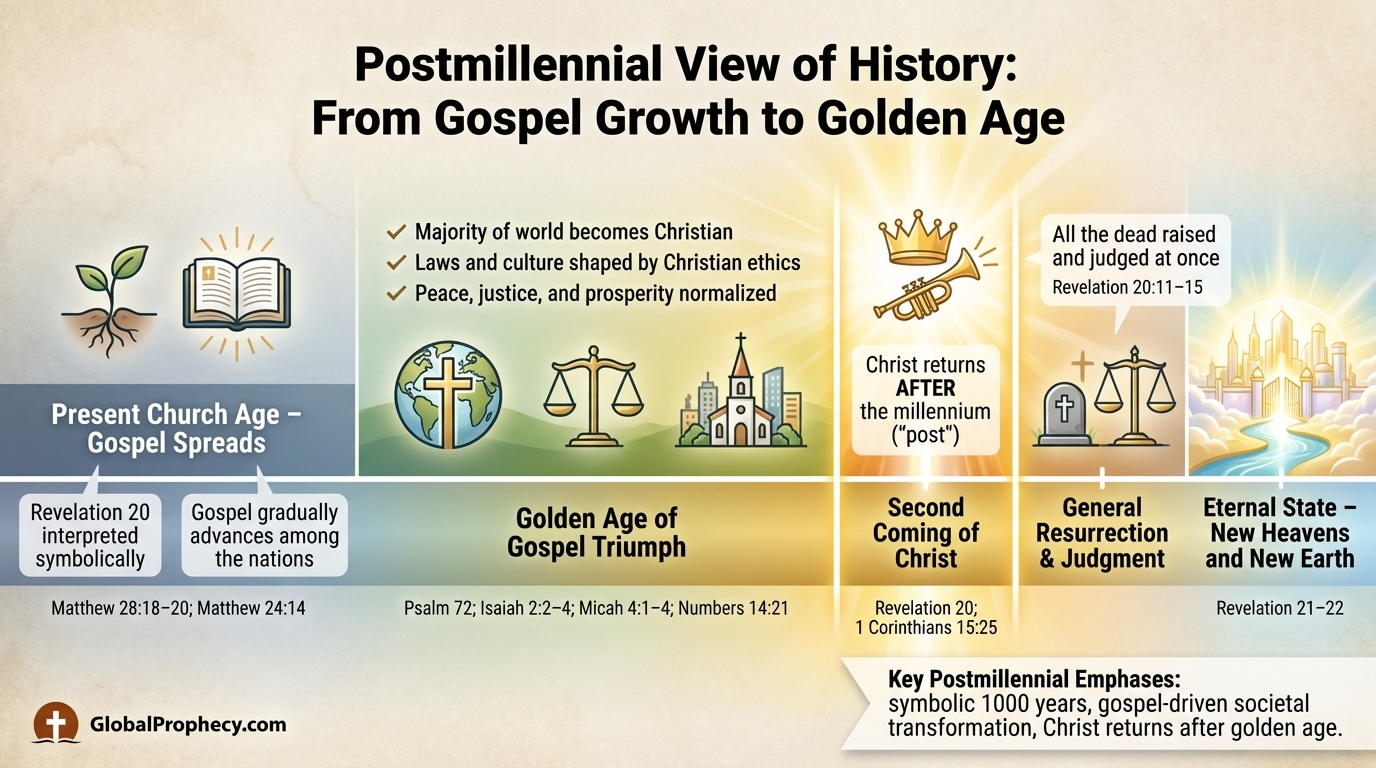

Postmillennialism teaches that:

- The “millennium” of Revelation 20 is a long, symbolic period, not a literal thousand years.

- This period corresponds broadly to the church age, or at least to its final “golden age.”

- During this time, the gospel will triumph to such an extent that:

- Most of the world’s population becomes Christian.

- Christian ethics shape law, culture, economics, and politics.

- Peace, justice, and prosperity become the global norm.

- Christ returns after (“post”) this millennial era to:

- Raise all the dead (general resurrection).

- Conduct a general judgment.

- Inaugurate the eternal state (new heavens and new earth).

As Loraine Boettner famously defined it:

“…the world eventually is to be Christianized, and … the return of Christ is to occur at the close of a long period of righteousness and peace commonly called the ‘Millennium’.”

Historically, postmillennialism:

- Was scarcely present in the early church, which was overwhelmingly premillennial.

- Gained prominence especially in the 18th and 19th centuries, amid Enlightenment optimism, scientific progress, colonial expansion, and missionary expansion.

- Suffered major decline after World Wars I and II, when global events contradicted its optimism.

- Has seen a limited resurgence in recent decades through movements such as theonomy / Christian reconstructionism, some forms of dominion theology, and segments of reformed theology.

3. Main Biblical Arguments Used by Postmillennialists

Postmillennialists appeal to several biblical strands to support the idea that the church will Christianize the world before Christ returns.

3.1. Great Commission and Worldwide Success of the Gospel

Postmillennialists argue that Matthew 28:18‑20 and Matthew 24:14 imply not only worldwide proclamation but worldwide conquest by the gospel:

“Go therefore and make disciples of all nations…”

— Matthew 28:19

They reason that since Christ has “all authority” and promises to be with the church to the end, the Great Commission must succeed in a dominant, global sense—a Christianized world.

3.2. Parables of Growth: Mustard Seed and Leaven

Postmillennialists appeal to Matthew 13:31‑33:

- The mustard seed growing into a large tree.

- The leaven spreading through the whole lump of dough.

They understand these as teaching the gradual but inevitable expansion of the kingdom until it pervades the entire world and its institutions.

3.3. “Golden Age” Prophecies in the Old Testament

They point to OT texts that portray earth-wide righteousness and peace:

- Psalm 72; Isaiah 2:2‑4; Isaiah 11:6‑9; Micah 4:1‑4

- Numbers 14:21: “all the earth shall be filled with the glory of the LORD.”

These are taken to describe a future golden era in history, prior to the eternal state, produced by the progress of the gospel.

3.4. Worldwide Salvation Texts

Passages such as:

- Romans 11:25‑26 (“all Israel will be saved”),

- Revelation 7:9‑10 (a great multitude from every nation),

are used to suggest that the majority of humanity, not a remnant, will eventually come to faith.

3.5. Symbolic Interpretation of “Thousand Years”

Postmillennialists agree with amillennialists that Revelation 20 is symbolic:

- “A thousand years” = a long, complete period, not a literal duration.

- Satan’s “binding” (Rev 20:1‑3) is taken to mean his progressive loss of influence as the gospel advances.

4. Biblical and Theological Problems with Postmillennialism

From a premillennial, literal–grammatical reading of Scripture, several fundamental difficulties arise.

4.1. The Timing and Nature of the Kingdom

Postmillennialism places the climactic triumph of the kingdom before Christ’s second coming. Yet the New Testament consistently associates the manifest, visible rule of Christ over the nations with His return in glory:

- In Acts 1:6‑7, the disciples ask, “Lord, will you at this time restore the kingdom to Israel?” Jesus does not deny a future restoration; He denies them knowledge of its timing, then sends them out as witnesses in the present age.

- Matthew 19:28 and Luke 22:28‑30 promise the apostles they will sit on twelve thrones judging the twelve tribes of Israel—something nowhere fulfilled in church history, but fitting a future, earthly reign.

- Revelation 19–20 presents a clear sequence:

- Christ’s visible return and defeat of His enemies (Rev 19:11‑21).

- Then (20:1) Satan is bound for a thousand years.

- The resurrected saints reign with Christ for that period (20:4‑6).

- Only after this millennium come the final rebellion, final judgment, and eternal state.

The most natural reading is that the millennium follows Christ’s return—not that it precedes it and is produced by the church.

4.2. The Binding of Satan

Postmillennialists claim Satan is already bound in such a way that he cannot “deceive the nations” (Rev 20:3), allowing for the gospel’s global triumph.

But this clashes with the New Testament’s description of Satan’s current activity:

- He is “the god of this world” who blinds the minds of unbelievers (2 Corinthians 4:4).

- He “prowls around like a roaring lion, seeking someone to devour” (1 Peter 5:8).

- He is “the whole world’s deceiver” (Revelation 12:9), and his deception intensifies in the last days (cf. 2 Thessalonians 2:9‑10).

The language of Revelation 20:1‑3—thrown into the Abyss, shut and sealed over him—depicts a total removal from earthly influence, not a partial restriction. Nothing like this has yet occurred in history. To call the present era the time when Satan “will not deceive the nations any longer” (Rev 20:3) is exegetically impossible.

4.3. Is the World Getting Better?

Postmillennialism is characterized by an optimistic view of history: the gospel will so transform society that evil becomes marginal.

However, key New Testament passages predict escalating evil and apostasy before Christ’s return:

- Matthew 7:13‑14: few enter the narrow gate; many go to destruction.

- Matthew 24:4‑12: deception, lawlessness, and persecution increase; “the love of many will grow cold.”

- Luke 18:8: “When the Son of Man comes, will he find faith on earth?”

- 2 Timothy 3:1‑5, 12‑13: “in the last days there will come times of difficulty… evil people and impostors will go from bad to worse.”

- 2 Thessalonians 2:3‑4: before the day of the Lord there will be “the rebellion” (apostasy) and the revelation of “the man of lawlessness.”

The book of Revelation likewise portrays the nations raging, persecution of the saints intensifying, and global judgments falling before Christ comes in glory—not a stabilized Christian civilization.

While God may grant seasons of revival and localized societal impact, there is no biblical warrant to expect a worldwide Christian golden age prior to Christ’s return.

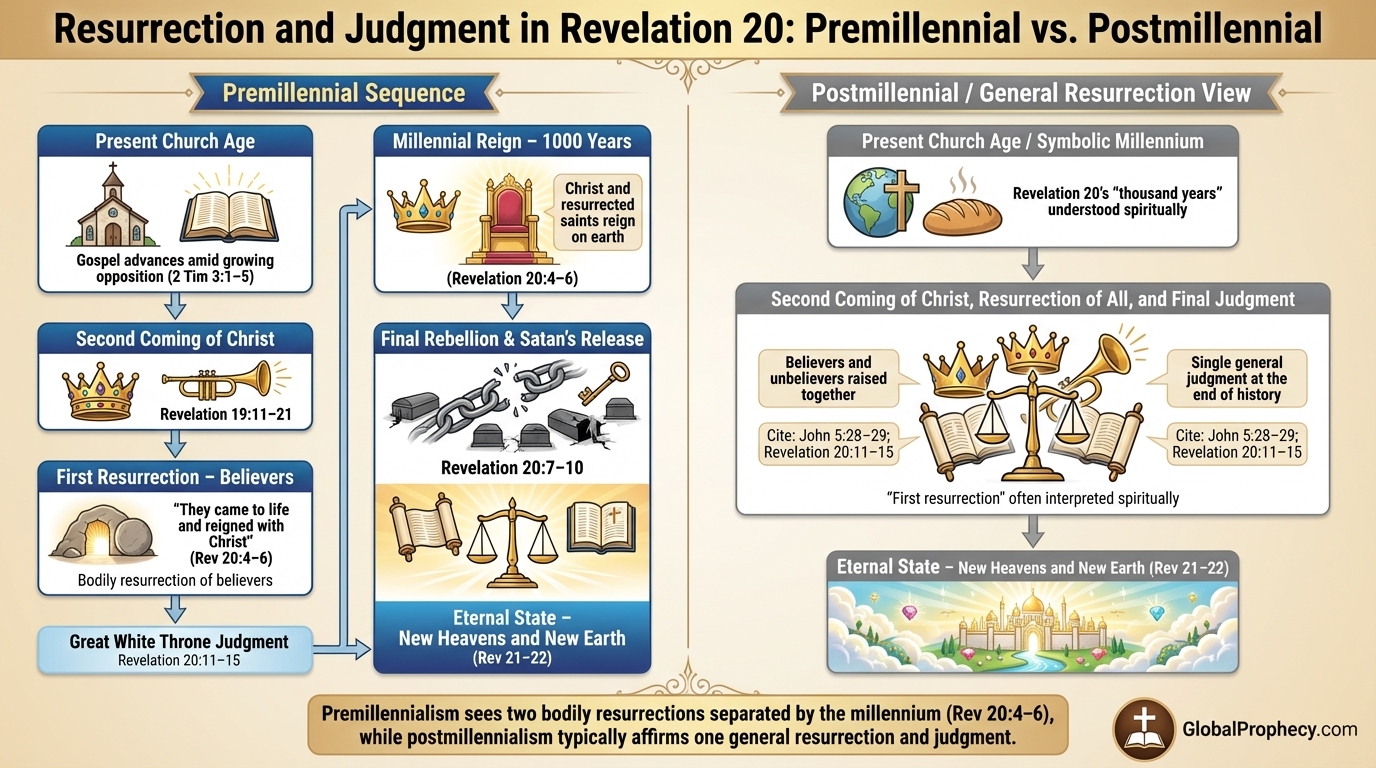

4.4. The Structure of Resurrection and Judgment

Postmillennialism collapses resurrection and judgment into a single, general event at the end of history. In doing so it must reinterpret Revelation 20:

- The “first resurrection” (20:4‑6) is taken as spiritual (conversion or the believer’s entrance to heaven).

- The “rest of the dead” coming to life (20:5) is taken as the only literal, bodily resurrection.

But this is exegetically strained:

- The same verb “came to life” (ezēsan) is used for both groups (20:4 and 20:5).

- The noun “resurrection” (anastasis, v. 5) is used 41 of 42 times in the NT for bodily resurrection.

- Nothing in the context suggests a switch from spiritual to physical meaning.

The straightforward reading: there are two bodily resurrections, separated by the millennium—first of believers to reign with Christ, later of unbelievers for final judgment. This pattern fits premillennialism, not postmillennialism.

4.5. Israel, the Church, and the Covenants

Most postmillennialists, standing in a covenant-theological tradition, blur or collapse the distinction between Israel and the church:

- Promises of land and kingship to Abraham and David are said to be fulfilled spiritually in the church.

- Thus there is no need for a future, earthly reign of Christ in which national Israel is restored.

Yet Scripture treats the Abrahamic and Davidic covenants as unconditional and irrevocable:

- The land was promised as an “everlasting possession” to Abraham’s seed (Genesis 17:7‑8).

- God swore that David’s throne and dynasty would be established forever (2 Samuel 7:12‑16; Psalm 89:30‑37).

- Paul insists that Israel’s current hardening is temporary and that “the gifts and the calling of God are irrevocable” (Romans 11:25‑29).

A literal fulfillment of these covenants—Christ reigning from David’s throne in Jerusalem, Israel restored and blessed among the nations—fits naturally within a future millennial kingdom, not within a church-driven golden age before Christ returns.

4.6. Hermeneutics: Literal vs. Spiritualized Fulfillment

Postmillennialism depends on a selective “spiritualizing” of prophetic texts:

- OT kingdom promises are reinterpreted as largely fulfilled by the church in this age.

- The “thousand years” of Revelation 20 are symbolic, while other numbers (144,000; 1,260 days; 42 months) are regularly treated as literal or at least definite.

Yet the pattern of biblical fulfillment is instructive:

- Prophecies of Christ’s first coming (Bethlehem, virgin birth, Davidic lineage, suffering, resurrection) were fulfilled literally.

- It is methodologically consistent to expect the second coming and kingdom prophecies to be fulfilled in the same way—literal return, literal reign, literal restoration.

When the plain sense yields a coherent eschatological picture (as premillennialism does), resorting to extensive spiritualization is not only unnecessary but distorts the text.

5. Practical Implications: Mission Without Illusions

Critiquing postmillennialism is not a critique of:

- Zeal for missions,

- Desire for cultural transformation,

- Confidence in the power of the gospel.

From a premillennial perspective, the church is called to preach the gospel to all nations, to influence society for righteousness, and to serve as “salt” and “light” in a decaying world—without the illusion that we will politically or culturally usher in the kingdom.

Scripture directs our ultimate hope not to a church-built civilization, but to the personal return and reign of Christ:

“…they will reign on the earth.”

— Revelation 5:10

“…they came to life and reigned with Christ for a thousand years.”

— Revelation 20:4

6. Conclusion

Postmillennialism offers an energizing vision: the world Christianized through the success of the gospel, followed by Christ’s return. Yet when tested by a consistent, literal reading of Scripture, several fatal problems emerge:

- The kingdom’s climactic manifestation is tied to Christ’s return, not to gradual historical progress.

- Satan is not now bound in the total way Revelation 20 describes.

- The New Testament foresees increasing deception and apostasy, not a steadily improving world.

- Revelation 20 teaches two bodily resurrections separated by the millennium, not one general resurrection.

- The Abrahamic and Davidic covenants still await their full, literal realization in a future earthly kingdom.

The church is indeed to labor, pray, and suffer for the advance of the gospel in every nation. But its hope for a truly righteous, global order rests not in its own cultural conquest, but in the appearing of the King who will personally establish His reign on earth.

“For he must reign until he has put all his enemies under his feet.”

— 1 Corinthians 15:25

That reign, in its fullness, awaits His return—not our success.

FAQ

Q: Does critiquing postmillennialism mean we should be pessimistic about missions and culture?

No. The New Testament commands global evangelism and calls believers to act as salt and light in every sphere of life. The critique is not against effort but against the expectation that the church will create a near-utopian global order before Christ returns. We labor faithfully, but we entrust the final establishment of the kingdom to the returning King.

Q: How does postmillennialism differ from amillennialism?

Both see the “thousand years” of Revelation 20 as symbolic and present rather than future. The key difference is optimism: postmillennialism expects the gospel to Christianize the world, while amillennialism generally expects ongoing conflict between good and evil until Christ returns, without a pre-parousia golden age.

Q: Is postmillennialism a heresy?

Historically, postmillennialism has been held by otherwise orthodox theologians and is best described as a serious error, not a damnable heresy. It misreads key prophetic texts and fosters unrealistic expectations about the course of history, but it does not necessarily deny core doctrines like the deity of Christ, the Trinity, or justification by faith.

Q: What is the main biblical problem with postmillennialism?

The central issue is its timing of the kingdom—placing the kingdom’s climactic victory before Christ’s return, rather than as a result of it. This forces postmillennialism to reinterpret the binding of Satan, the description of end-times apostasy, and the structure of resurrection in Revelation 20 in ways that conflict with the plain sense of the text.

Q: If the church won’t Christianize the world, what is our role in history?

The church’s calling is to proclaim Christ, make disciples, plant and strengthen churches, and live holy lives that display the coming kingdom. We should work for justice, mercy, and truth in every sphere, knowing our efforts are not in vain—but we recognize that only the returning Christ will decisively subdue all enemies and establish perfect righteousness on earth.

Frequently Asked Questions

Does critiquing postmillennialism mean we should be pessimistic about missions and culture?

How does postmillennialism differ from amillennialism?

Is postmillennialism a heresy?

What is the main biblical problem with postmillennialism?

If the church won’t Christianize the world, what is our role in history?

L. A. C.

Theologian specializing in eschatology, committed to helping believers understand God's prophetic Word.

Related Articles

Amillennialism Examined: Is the Church the Millennial Kingdom?

Amillennialism examined: is the church the millennial kingdom? Explore its claims, symbols, and a biblical critique of this end-times view.

What are the Marriage of the Lamb?

Marriage of the Lamb reveals Christ’s union with His church in Revelation 19. Explore its meaning, timing, and eternal significance in God’s plan.

Comparing the Millennial Views: Which View Is Biblical?

Millennial views compared: premillennialism, amillennialism, and postmillennialism. Examine key texts to see which view best fits Scripture.

What is the Millennium? The 1000-Year Reign of Christ

Millennium: the 1000-year reign of Christ explained. Discover its duration, nature, and prophetic significance in God’s future kingdom plan.